Hello there! Welcome to The Magpie, a newsletter that serves as a collection of shiny objects about writing, creativity, hopes, and obsessions. My current obsession is diaries and the people who write them. Since I started keeping one at age eight, my diary has been a place of exploration and intensity, of lists and favorite quotes, of ticket stubs and wildflowers. It is a place to remember and a place to dream.

My most recent book, The Leaving Season: A Memoir in Essays, is out now! I relied on decades of my own diaries to help me write this book. My next book focuses on historical diaries of women, famous and not, and why we continue to write—and read!—these archives.

This is a Show Me Your Diary interview, a series that explores diaries and the creatives who keep them. Every week, I ask a new person to give us a peek inside their diary process, complete with photos. Yes, we are very nosy!

Want to show me your diary, or know somebody who does? Send me an email—you can just reply to this newsletter. Let’s get started…

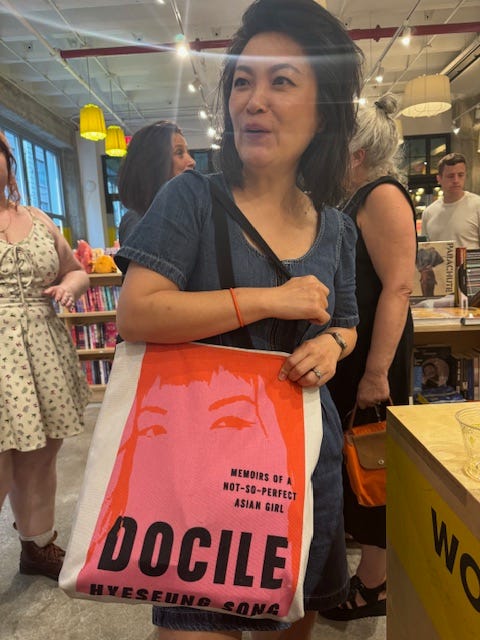

Today’s interview is with Hyeseung Song, artist and author of Docile: Memoirs of a Not-So-Perfect Asian Girl. I was first awed by Hyeseung at last year’s AWP conference in Kansas City during a panel on memoir called “It’s Me. Hi. I’m the Problem, it’s Me: Wresting with Your Former Self in Memoir.” She spoke in such a commanding way about the tough stuff, like how to present mental illness on the page, how to trust your own story, and confronting former selves on the page. I was excited to read alongside her a few weeks later at the UWS reading series Must Love Memoir (check out their Substack here), where she read to a transfixed crowd about the struggle of navigating clashing expectations through the lens of her daughter-mother story, taking on all of the taboo topics in one short reading, including depression, money, and first-generation family pain.

A few weeks later, at an event we did together about the Myths of the American Dream at the Powerhouse Arena in Brooklyn with Alissa Quart and Adelle Waldman, Hyeseung again wowed the crowd (and not only with her matching Docile tote!). And it is no wonder. In her memoir, Hyeseung writes frankly and beautifully about her struggles with depression and mental health. Growing up in Sugarland, Texas as the daughter of Korean immigrants, cultural and capitalistic expectations grind Hyeseung down until she is the perfect student, top of her class and going on to study at Princeton and Harvard, yet struggling to stay alive. Eventually, Hyeseung crumbles, entering a psychiatric center, where she finds for the first time that she is not alone in her mental health struggles and she slowly begins excavating a new life out of the wreckage. Art and expression is at the center of this new life; what follows is a riveting tale of creativity, healing, and love.

One of the most impactful parts of Docile for me was the complicated, powerful relationship Hyeseung draws between herself and her mother, whose presence is also felt in our discussion for the Show Me Your Diary interview. Below, we talk about grief, strength, and the connection between journals and making space for your own voice.

And, of course, she lets us peek inside some of her actual diaries!

THE MAGPIE: Team Diary vs Team Journal? What do you like to call it?

HYESEUNG SONG: I bought my first notebook at the Scholastic Book Fair when I was about seven. Small rhinestones in the shape of a unicorn studded the black velvet cover. It was so fabulous it took me a few days and a lot of courage to make my first entry, which started “Dear Diary.” As I grew into adulthood, the epistles lost their salutation along with any supposed externalized reader of my thoughts, and the page became more a place to unfurl my voice, wander through confusion, talk dreams, track goals. The writing became a daily record of self-reflection, and I started referring to the notebooks as journals, for the days (jours).

How long have you kept a diary?

Since I was in first or second grade. I was lucky: I had incredible elementary school teachers who encouraged personal writing and diary-keeping. My practice lagged through high school which was, to me, so much about earning visibility through external achievement. During the ninth to twelfth grades, what I thought about myself mattered very little. Had I given myself more space to address myself during that time—to take up space on a page—maybe things would have gone differently. I reprised the practice in college and have been consistent since then.

My Korean is now very shoddy, but even then, I could make out the sentences [in my mother’s journals] slowly if I wanted. It’s just that looking at her handwriting stops my heart.

What do you hope will happen to your journals once you are gone?

For this project, I got out some of my old journals to read (not for the faint of heart!). I picked one randomly, opening to the first entry, which happened to be dated March 26, 2017, eight years to this day. “I think time for journaling again,” I’d written. “There were still pages in the last notebook but it ended with Mom still alive and [it] did not seem right or desirable (?) to start up again from October 2016.”

My mother started the quick process of dying in October 2016; she was gone by the beginning of that November and with her death, reconfigured the life of our family, and my own existence. She herself left behind journals and the beginning of a memoir. She wrote in our native language. My Korean is now very shoddy, but even then, I could make out the sentences slowly if I wanted. It’s just that looking at her handwriting stops my heart.

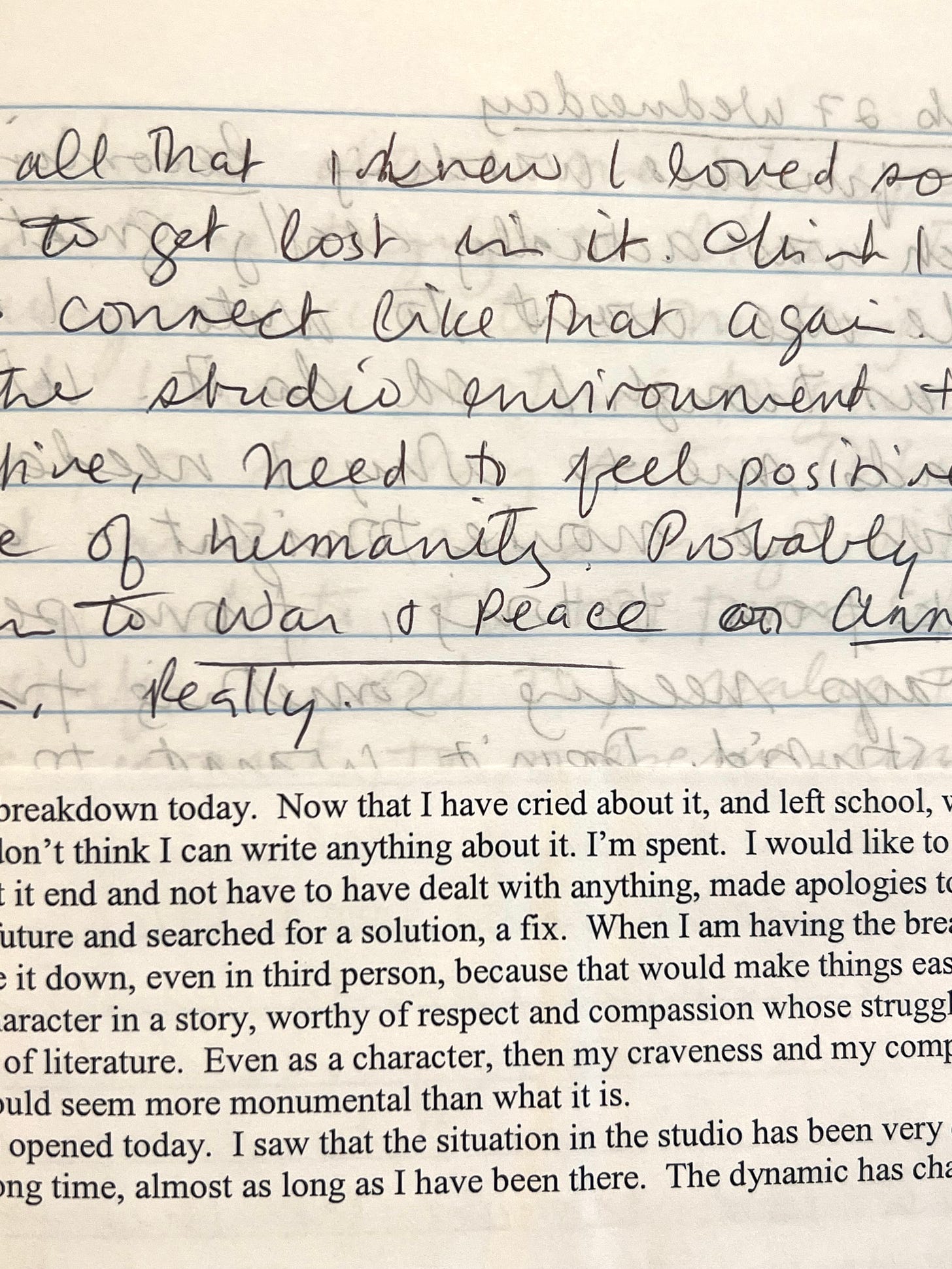

If the ones who survive me read my journals, I hope they understand they’re stepping into my own confessional booth. The entries are not particularly representative of how I felt at the time of recording—my adult journaling is confused problem-solving exercises in which I try to show my work, earn partial credit from myself. There is a good deal of complaining and generally being awful to myself, as well as a soupçon of Gratitude when I can alight on that shaky branch. If I am the monster, they would read my loneliness; if I am the innocent, they would certainly know my cunning.

They would see someone earnestly searching to move from one patch of confusion to temporary epistemic relief only to be plunged into colder waters of questioning and self-doubt. They would read my actual dreams—the figments of my subconscious flickering on the mental screen—and the parsing of the frayed edges of what I managed to remember upon morning. They would read the actual hopes and desires for my waking life. They would, if they loved me, know how much I fell short. I am dead, so it wouldn’t matter for me. But this person is alive, and maybe that gap would bring pain.

If the ones who survive me read my journals, I hope they understand they’re stepping into my own confessional booth.

How were you introduced to diaries or journals?

I don’t remember the first introduction, but I do remember the best. At the beginning of fifth grade, my teacher Ms. Jenkins gave each student a yellow spiral composition book, wide-ruled, with our name in blue marker on the front. I think we were allowed to write in cursive or print, and the class was given a little time everyday to journal.

On Friday afternoon, we’d pass up the notebooks to the front of the classroom and she’d pass them back on Monday morning having written smiley faces and nice comments in the margins—nothing negative or corrective. She was trying to introduce us to this exercise of personal writing. But because it was a diary, if you wanted to write something only for yourself, you folded down the pages you didn’t want to share, and Ms. Jenkins wouldn’t lift them.

Why do you keep a diary?

I keep a journal because my inner life is both sacred and curious to me. I tend to write within thirty minutes of waking, with my first cup of coffee—it’s a way to prepare myself to be in conversation with the world, once the journal is closed and I get on the phone or open my email. I do therapy and have for most of my adult life, but journaling is different. I think it’s through this consistent practice where I have shown up for myself and tried hard to puzzle out my life, by which I have become my best friend.

I think it’s through this consistent practice where I have shown up for myself and tried hard to puzzle out my life, by which I have become my best friend.

It's thanks to these journals that I am able to recognize the overarching fact of my struggle with the same one or two fundamental human issues from which every other stems. Over the years of entries, I sometimes mark little progress, even regression on these issues. But I know that my life—the basic human life as well as the hungry creative aspects of it—benefits from this practice.

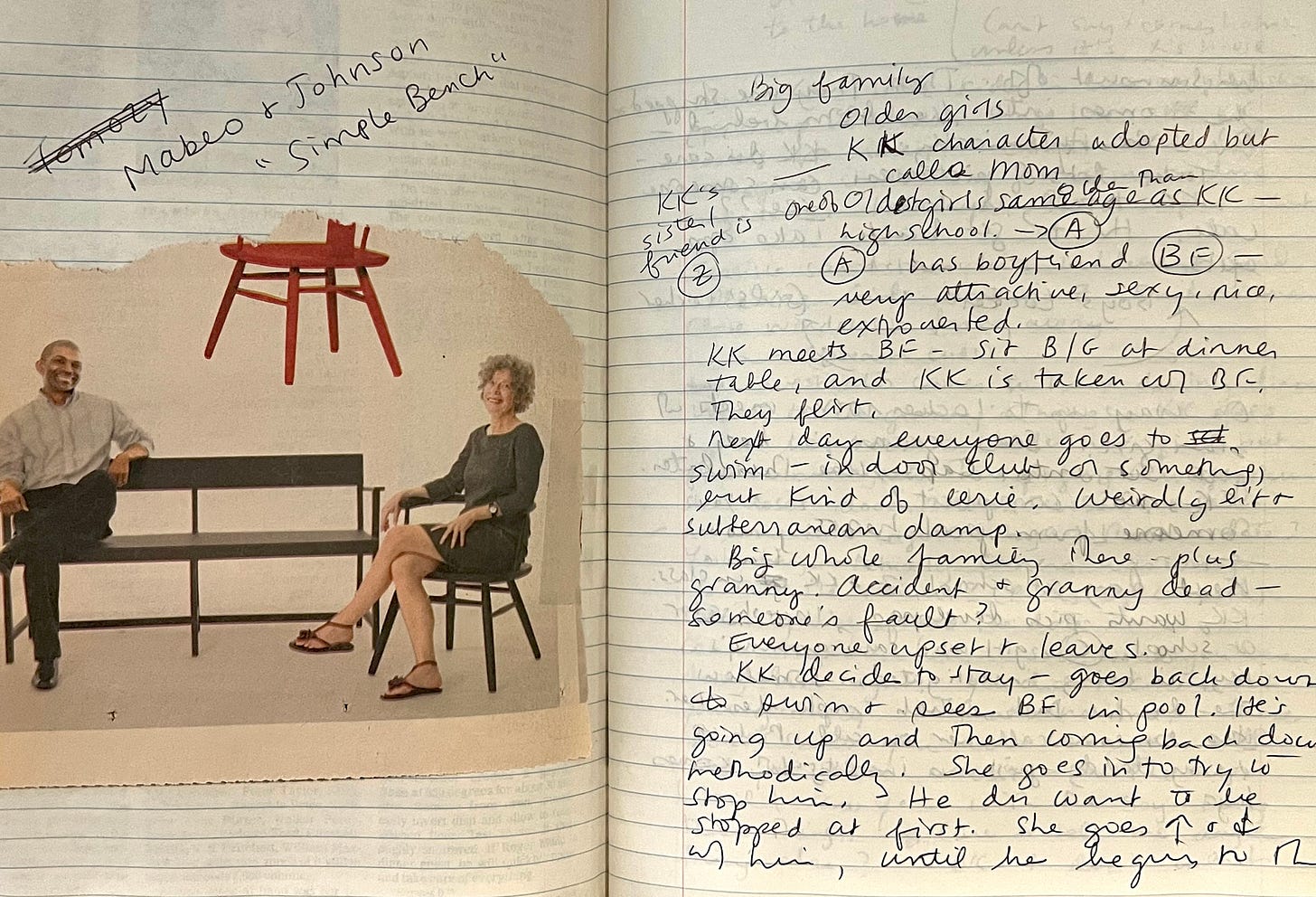

For me, because I tend towards sad but swift rumination, the practice of journaling slows down the pace; because I write on paper, instead of type into a digital space, it’s easy for me to doodle if I need to (I’m a painter by trade); it is a record I can revisit to see what themes were at the top of mind at any time: I am tired, I hope I can sleep, I hope I am not sad in the afternoon, I am angry, I wish I could forgive this person, I wish I could forgive myself, I wish I didn’t want to die.

Has anyone ever read your diary, or have you read someone else’s?

I read once, by accident, a line from my ex-husband’s journal just as we started dating. He wrote that I was beautiful and kind, and that he knew we’d always be friends. I closed the notebook after that.

More About Hyeseung Song:

Hyeseung Song is a first-generation Korean American painter and the author of Docile: Memoirs of a Not-So-Perfect Asian Girl (pre-order the paperback, out 7/15/25!). Docile has been called a "savagely beautiful memoir" by David Henry Hwang, a "revelation" by Chloé Cooper Jones and was named a "Best Book" by Apple, Book Riot and "Most Anticipated" by Electric Literature, and more. Raised in Texas, Song studied philosophy at Princeton and Harvard Universities, and painting at the Grand Central Atelier in New York City. A two-time Greenshields award winner, TedX speaker, and resident artist of the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation of New Mexico, the Vermont Studio Center and the Alfred and Trafford Klots International Program, Song has also taught at the Maryland Institute College of Art and the Fashion Institute of Technology. She is at work on a novel. Song lives in Brooklyn and upstate New York.

Social media: IG at @hyeseungs

Upcoming events:

Bookstock: Festival of Words Sunday, May 18 in Woodstock, Vermont: An event with Hana Park and Yahdon Israel.

Celebrating AANHPI Storytellers! Wednesday, May 21 at PRH in NYC: In honor of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, WMG invites you to join us for an exceptional panel featuring distinguished AANHPI literary voices, including Hyeseung Song, Katie Kitamura, Megha Mujumdar, and Qian Julie Wang, moderated by Vicky Nguyen.

Both/And: Five Writers on the Intersection of Mental Health & Identity Thursday, May 22 at P&T Knitwear, NYC: "Five Writers on the month of May: The Intersection of Mental Health Awareness and Asian American Heritage" (6.30-8 PM), with Hannah Bae, contributor to the anthology (Don't) Call Me Crazy: 33 Voices Start the Conversation about Mental Health, Nina Sharma, author of The Way You Make Me Feel, Prachi Gupta, author of They Called Us Exceptional, Helena Rho, author of American Seoul and Stone Angels, moderated by Hyeseung Song.

Thanks for reading The Magpie by Kelly McMasters! As always, more of what I’m up to can be found on my website, and you can follow me on Instagram for day-to-day updates.

Buy The Leaving Season here, Welcome to Shirley here, Wanting: Women Writing About Desire here, and This is the Place: Women Writing About Home here.

I loved Docile but this makes me love it even more!

Thank you so much for including me (and my journals) in this series, Kelly! Talk about interiority! I also loved the walk down memory lane with you!