Hello there! Welcome to The Magpie, a newsletter that serves as a collection of shiny objects about writing, creativity, hopes, and obsessions. My current obsession is diaries and the people who write them. Since I started keeping one at age eight, my diary has been a place of exploration and intensity, of lists and favorite quotes, of ticket stubs and wildflowers. It is a place to remember and a place to dream.

My most recent book, The Leaving Season: A Memoir in Essays, is out now! I relied on decades of my own diaries to help me write this book. My next book focuses on historical diaries of women, famous and not, and why we continue to write—and read!—these archives.

This is a Show Me Your Diary interview, a series that explores diaries and the creatives who keep them. Every week, I ask a new person to give us a peek inside their diary process, complete with photos. Yes, we are very nosy!

Want to show me your diary, or know somebody who does? Send me an email—you can just reply to this newsletter. Let’s get started…

Today’s interview is with Stanley Stocker, a fiction writer and fellow journal enthusiast from Washington, DC. He is also the first person whose journals I’m highlighting here after meeting through this very Substack series. (I’m working on a special reader’s edition so I can highlight more of your journals—stay tuned for a call for submissions very soon!)

I knew I had to include Stanley’s journals in SHOW ME YOUR DIARY after reading this interview with Stanley in Susurrus Magazine about his writing process. I’ve never come across Stanley’s habit of decorating his fresh notebooks with images….before he starts writing. So he writes into the images, rather than the images being inspired by the writing. I had to know more.

The images themselves also captured me. His novel-in-progress takes place in the South, a place he’s never lived, but by which he is fascinated. In the Susurrus interview, he talks about his characters who live in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, one of the all-Black towns that emerged across the South after the Civil War. “Whether it’s free people in an all-Black town or men who are imprisoned, how do they still find joy in their lives? Because we always find a way.” The images seem directly related to this impulse—to find joy—both the finding and the places where joy may be found.

Through my research, I’ve seen diaries act as this kind of conduit for people across time and geography. Joy requires attention. This is also the gift of the journal.

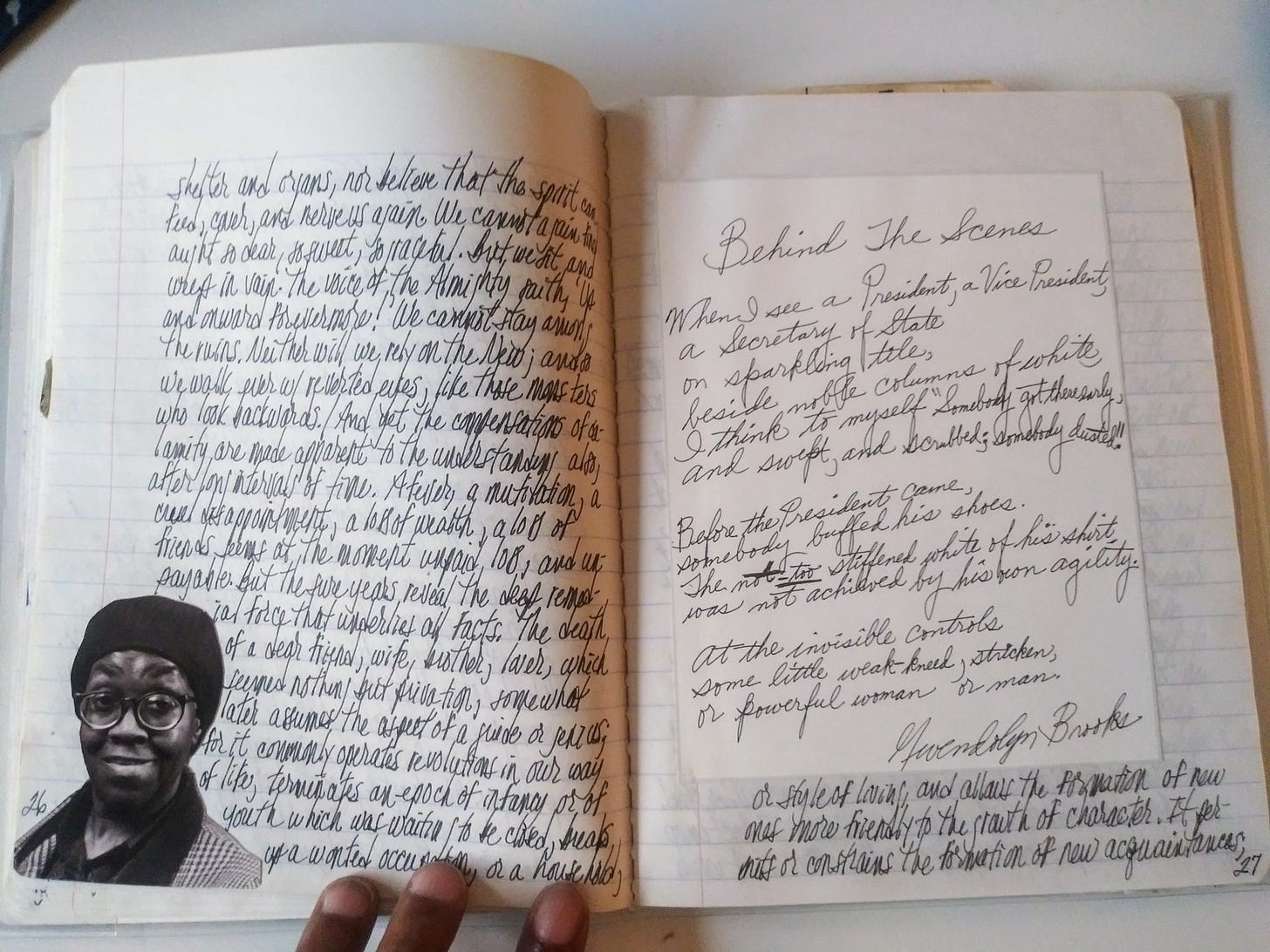

As I learned more about Stanley’s creative process and his writing, the work of a favorite writer of mine came to mind: Aracelis Girmay. In “From Woe to Wonder,” a gorgeous, devastating essay (first published in The Paris Review and reprinted in my anthology co-edited with Margot Kahn, Wanting: Women Writing About Desire), Aracelis recalls Gwendolyn Brooks, as Stanley does in one of his diary entries here (read to the end!). Here is one of my favorite lines from her essay: “Part of what I understood was that language could help us to live and could help us to die.” This line feels akin to Stanley’s endeavor to capture joy in his fiction, as well as that private space of his journals.

For this interview, we talked about the ways a peripatetic childhood can inspire a constant home in journals, the beauty of the humble marble notebook, and the alchemy of transcribing the words of other writers by your own hand into your journal.

And, as always in Show Me Your Diary, Stanley gives us a peek inside some of his actual diaries…welcome!

THE MAGPIE: Team Diary vs Team Journal? What do you like to call it?

STANLEY STOCKER: I’m Team Notebook. Maybe it’s because I feel like a perpetual student or because often I’m literally taking notes based on something I’ve read. Also, the root words of “diary” and “journal” both relate to back to “day” and I don’t write in my notebook every day.

How long have you kept a journal?

It’s been about 25 years now. I started well into my adulthood. It coincided with a period when I quit my lawyer job to write and read and I felt like I needed someplace to gather all the things I was thinking and reading. Even when I went back to practicing law, I continued using notebooks. Growing up my family moved from place to place in Philadelphia a lot. I think my eldest brother counted twenty-something different places before he turned 18. Having something that is always mine and always with me is probably related to that movement in my childhood.

Having something that is always mine and always with me is probably related to that movement in my childhood.

What do you hope will happen to your journals once you are gone?

That’s a tough one. I’m not sure I’ve thought about it much. For now they serve as supportive “scaffolding” of a kind for my fiction and learning. After I’ve accomplished what I want to in my writing I’m not sure I’ll need them, but I do hope they stay together like a little family and someone interested in really knowing me will appreciate them.

I think of being able to go to the Library of Congress and reading Whitman’s notebooks. But after all, I’m like a caterpillar speculating about what will become of my caterpillar things after I’ve become a butterfly. It’s fun to speculate, but I will have put away my caterpillar things when that time comes and what will be will be.

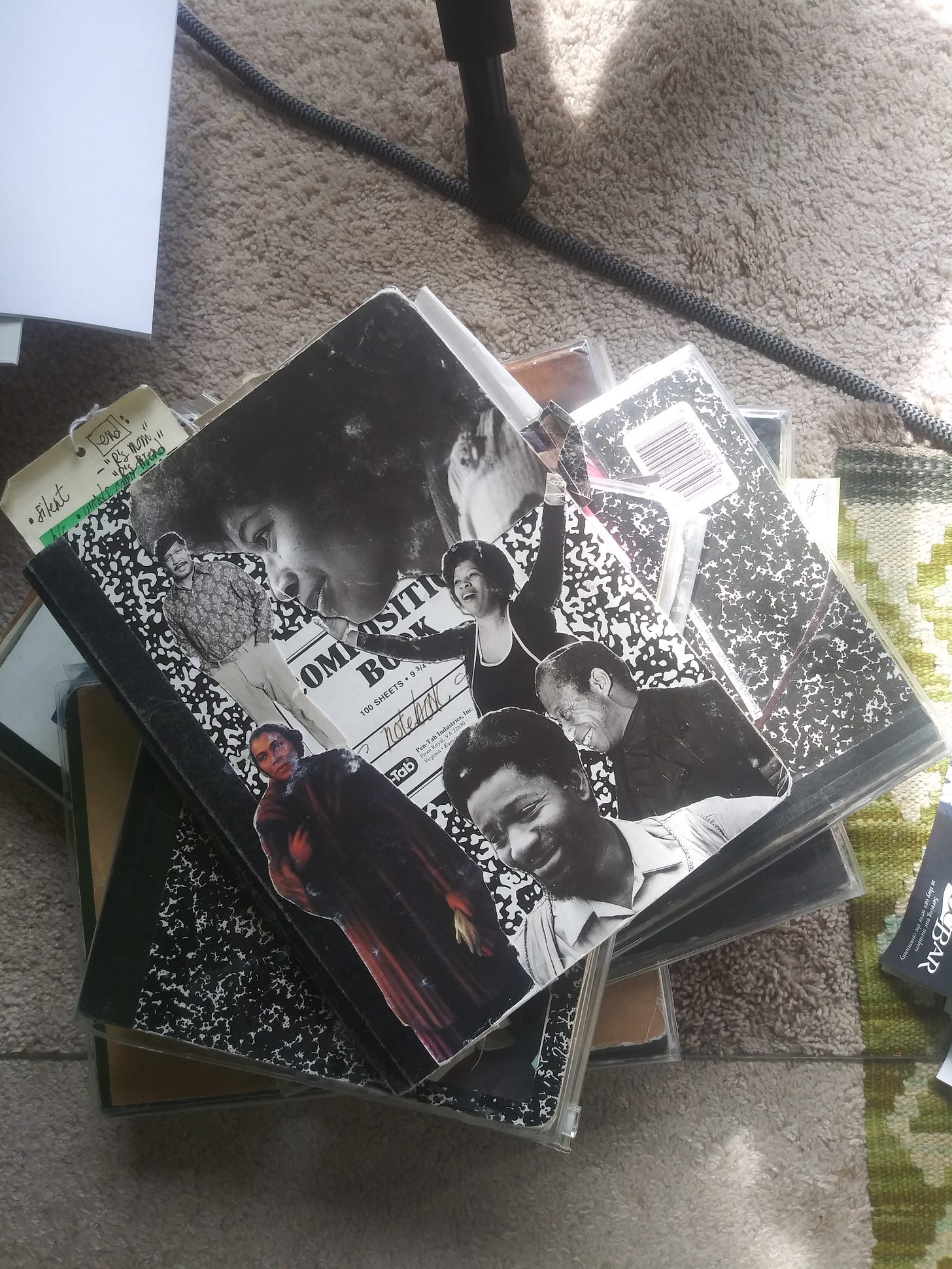

What is your favorite kind of journal to use?

I’ve always loved the black and white marbled composition notebooks that I used as a child. The spaces between the lines are broad and generous. The paper feels good to the touch. I love the multiplication tables in the back and the measurement charts, as if they stand ready for some wild exploit that will require me to be able to convert kilograms to ounces. I need something that says, All Things are Welcomed Here. That’s what my notebooks are to me—a place where anything goes.

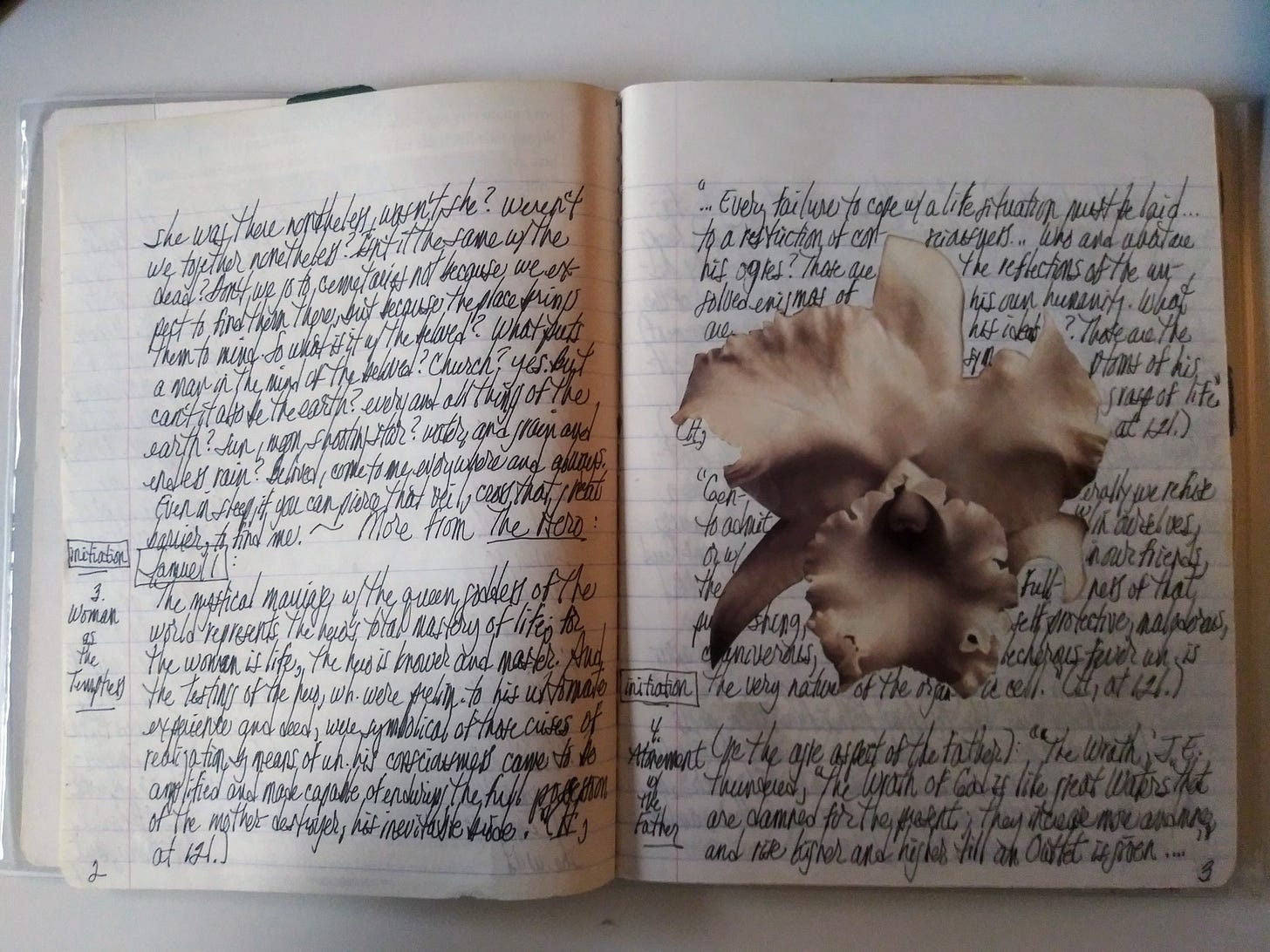

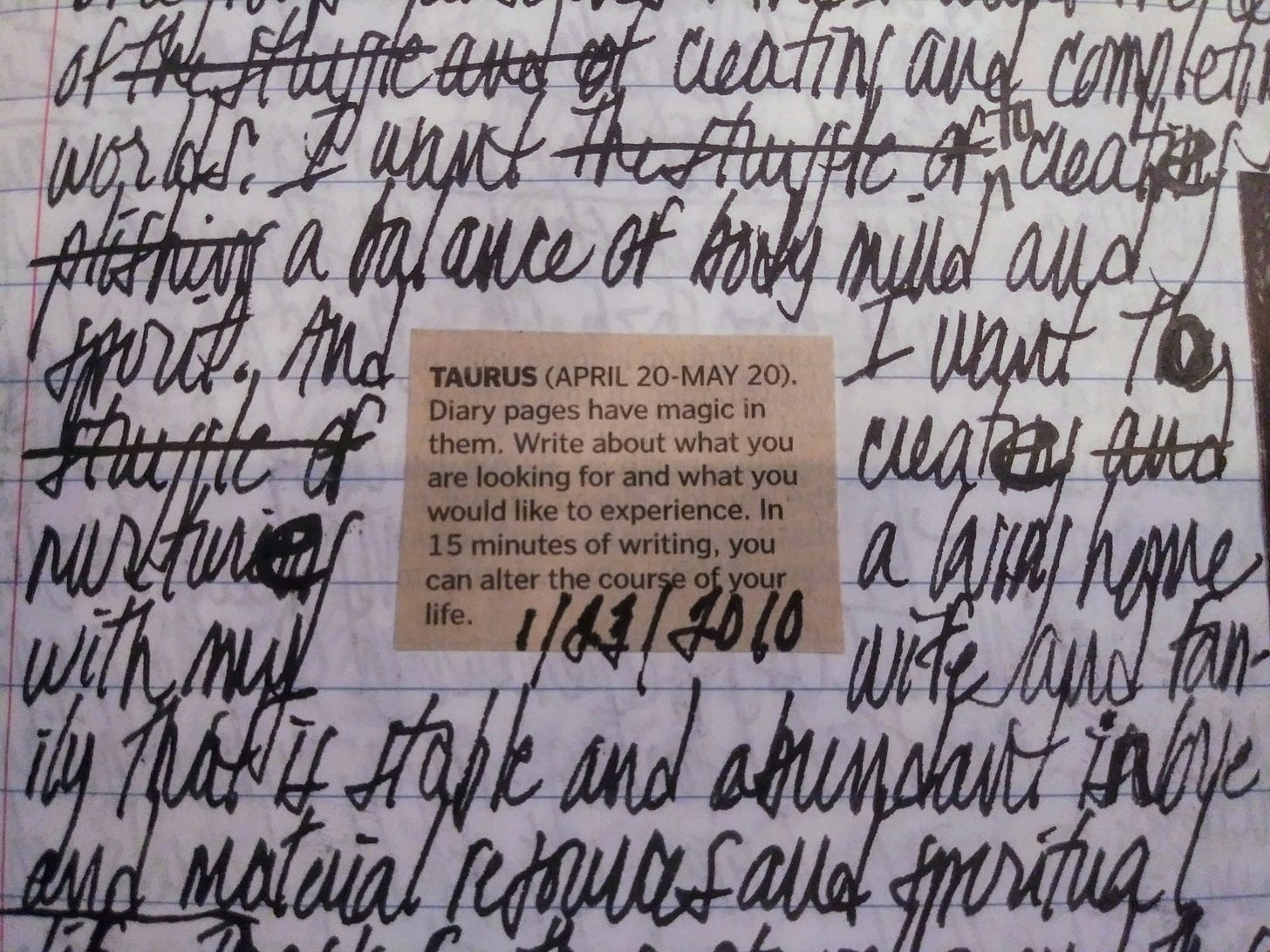

I pick them up at the CVS for a few dollars each then decorate them with images from magazines. Folk art magazines, fine art magazines, literary magazines, museum catalogues. Recently, I was sent the most beautiful catalogue of wood block prints from Japan. The images are heaven. These are images of original prints from decades and sometimes a century or more ago. I love deciding what to put on the covers and what images to cut out and paste in the notebooks. I like to find a rhythm to the images that work together and often speak to each other across the pages. Sometimes it reminds me of what I imagine it must feel to curate a literary magazine – picking pieces that will work well together.

One of the strange things I’ve sometimes observed is the uncanny correspondence between an image that I long ago placed in the notebook and by the time I get to that page what I’m writing about is related to the image when I turn the page. That happened with the 9/11 attacks. I turned the page that morning and there was an illustration of an enormous head of a baby with a look of horror on its face.

I’ve always loved the black and white marbled composition notebooks that I used as a child. The spaces between the lines are broad and generous. The paper feels good to the touch. I love the multiplication tables in the back and the measurement charts, as if they stand ready for some wild exploit that will require me to be able to convert kilograms to ounces.

When do you write in your journal?

These days almost always at night after our son goes to bed. In the earlier years before our son was born I carried my journal everywhere I went, but now though it’s with me most days, I usually write at night when the house is quiet. Usually a couple times a week or sometimes it can be every night if I’m reading something and taking notes on it. Usually I’m taking notes on something I’m trying to understand. Right now I’m jumping between the Bible and Jung and other writers on the human impulse to religion. But just as much, I also use my notebooks for fiction that comes to me or as a place to jot down ideas for stories that I can come back to later.

What do you do with your journals? Where do you store them?

I keep them stacked on a little shelf next to my desk.

Has anyone ever read your diary?

I shared some of them with a writer friend once, but I think they gave up because my handwriting was so hard to read! (Or maybe there was something they read that they didn’t like. Who knows?)

Who are you writing to in your diary?

Definitely myself. Things I want to remember. It’s a place sometimes for things that correspond to one another that I want to remember. Sometimes making a connection between two seemingly disparate things can feel like pieces of a puzzle coming together.

A while back I thought of two things that seemed to be speaking to each other across time. One was a passage from Melville from Moby Dick: “Where lies the final harbor, whence we unmoor no more? In what rapt ether sails the world, of which the weariest will never weary? Where is the foundling’s father hidden? Our souls are like those orphans whose unwedded mother dies in bearing them: the secret of our paternity lies in their grave, and we must there to learn it.” The other was a line from St. Augustine: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” Melville seems be posing the question and Augustine seems to be responding across time, more than a thousand years earlier.

Well, sometimes a notebook is the place to remember and I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.

Now, whether that’s a satisfactory response is another question, but a notebook is a perfect place to remember that kind of thing. Frost said, “Earth’s the right the place for love: I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.” Well, sometimes a notebook is the place to remember and I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.

As a writer, how is your voice different in your journal than on the page?

Sometimes the voice is identical. A passage will come to me and it’ll go into a piece of fiction virtually unchanged. But that’s rare. When it does it’s almost like it’s been formed somewhere else and I’m alerted that I have to grab a notebook to write down what I’ve received.

Other times the voice literally is the voice of another writer because I’m writing down what another writer has said about something and I’m like a scientist gathering data and comparing it to other things to try to come up with a coherent view of something or at least a list of questions I have about something. Other times you just want to memorialize the beauty of a passage.

Today I opened an old notebook to a random page and found the passage in Moby Dick where the Pequod has come upon another ship, The Rachel, in search for a lost boy: “She was Rachel, weeping for her children, because they were not.” Or where Ahab talks to Starbuck in the midst of a “mild, mild wind” and a “mild looking-sky” where “the air smells now, as if it blew from a far-away meadow.” Sure, I could reach over and pull the novel from the shelf and find the passage, but there’s something about seeing the words in your own hand that makes them your own; you take ownership of them in a way you can’t when you just read them in the book.

That’s the alchemy of a notebook: it can turn gold into even more precious gold.

More About Stanley Stocker:

Born and raised in Philadelphia, Stanley Stocker is a winner of a PEN America/Dau Prize, a Creative Power Award, and a finalist for The Best Spiritual Literature Award—Fiction. His work has appeared in or is forthcoming in Harvard Review, African-American Review, Arkansas International Review, Best Debut Short Stories, and elsewhere.

Listen to Stanley talking about short story writing:

Short Story Today podcast

Find Stanley online:

on bluesky at @stanleystocker

on instagram at @stanleystocker

Thanks for reading The Magpie by Kelly McMasters! As always, more of what I’m up to can be found on my website, and you can follow me on Instagram for day-to-day updates.

Buy The Leaving Season here, Welcome to Shirley here, Wanting: Women Writing About Desire here, and This is the Place: Women Writing About Home here.

I look forward to your newsletter every week. So much goodness here. I love the idea of adorning the pages prior to writing. I am also a copier of words.

LOVE that you talked to Stanley, who I met a few years back at the Cuttyhunk Residency. (and cannot wait until his novel is published. Gorgeous writer!)